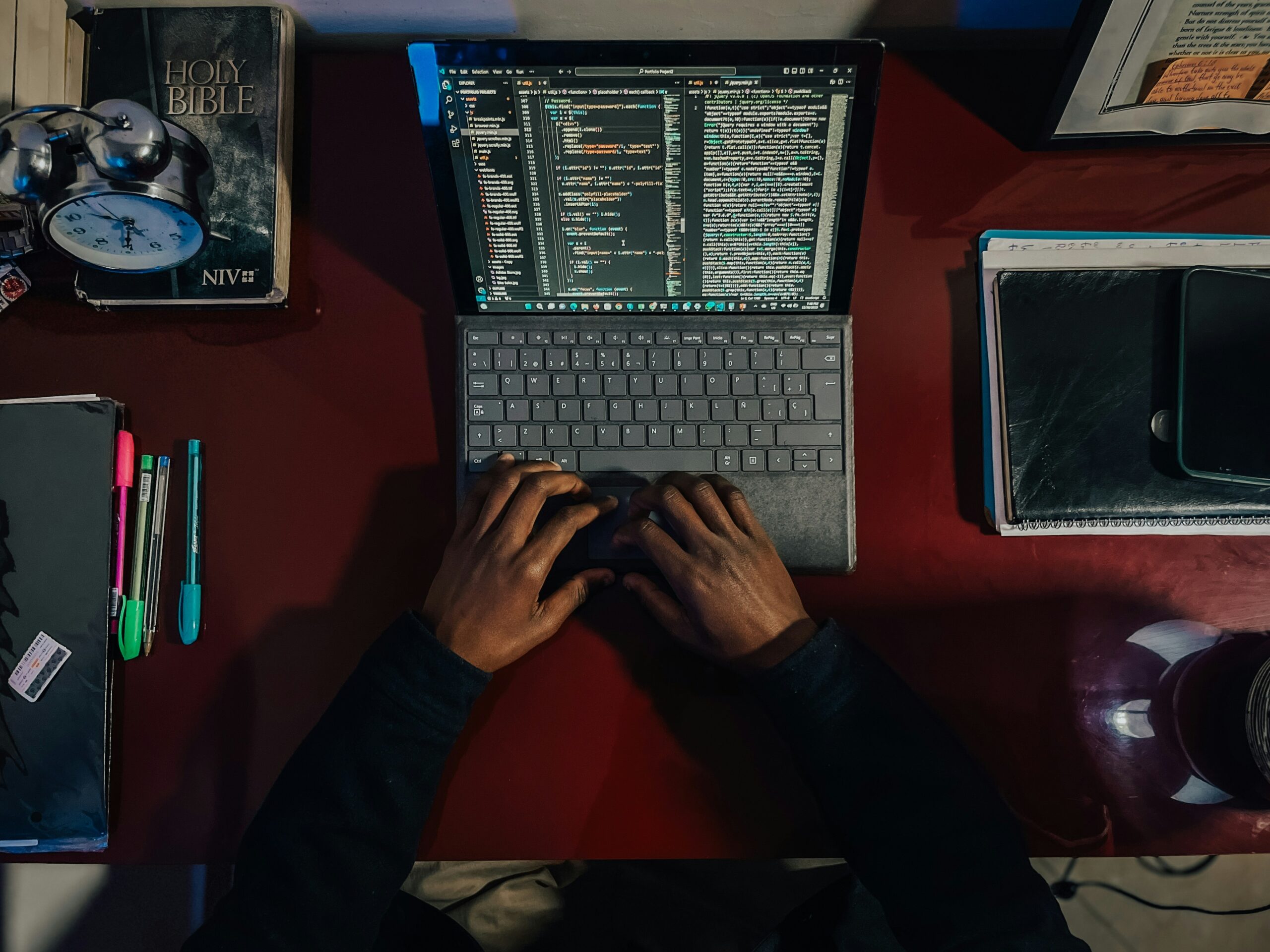

An IT professional confronts the cost of always-on design

Spending most of my career building robust systems, with 360 degree defense and protection, meant to scale distributed architectures that stay available no matter how many users log on, no matter how long they stay. Downtime is failure. Friction is the enemy. Engagement is success.

None of that prepared me for watching my teenage nephew sit on the couch, phone inches from his face, thumb moving with mechanical precision while the room around him disappeared.

And this in the age of brain-rot is a trigger for anxiety and panic mode because what the time has taught is that disconnection is the new luxury and research helps with this new narrative1.

And as any good parent would do even though I am not directly parenting at the moment, asked what he was watching.

“Nothing,” he replied, without even looking up.

He wasn’t being evasive. He was being accurate.

That answer unsettled me more than if he’d named a game or a video or a platform. “Nothing” is what happens when content stops being an experience and starts functioning like infrastructure that is always there, always flowing, no beginning, no end.

Which kicked my gut! I had helped build versions of it. The machinery of doom-scrolling, the introducing element of brain-rot indeed.

Systems That Never Let You Leave

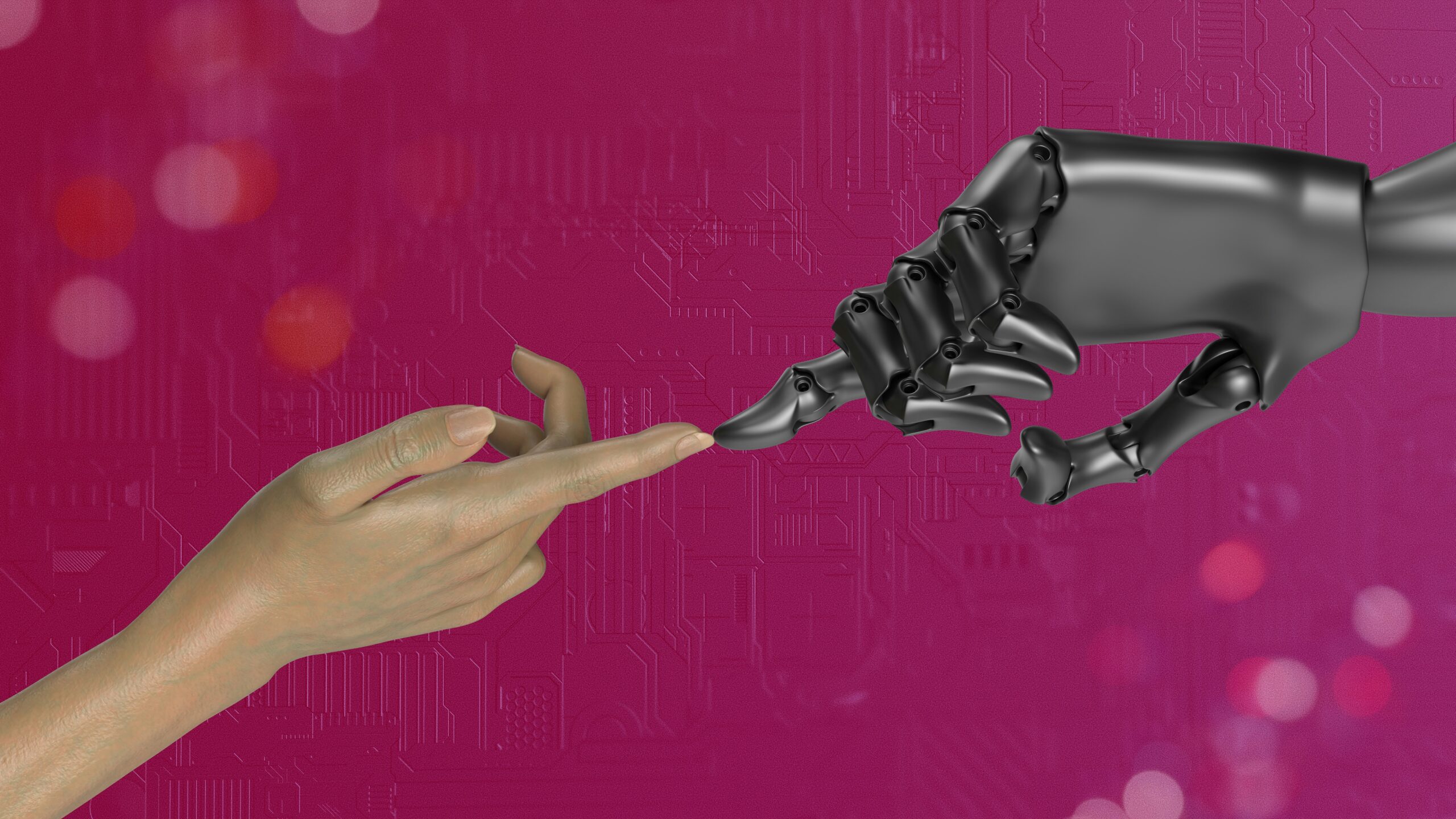

In the age of Information and economy that relies heavily on online presence, we optimize for uptime, throughput, and retention. We design systems that anticipate demand, remove pauses, and recover seamlessly from interruption. The goal is continuity.

Modern consumer platforms apply the same logic to human attention.

Autoplay. Infinite scroll. Algorithmic feeds tuned not for satisfaction, but for persistence. Each interaction is treated as a signal, each pause as a problem to be solved. A capitalistic approach to system design and exploitation of human psychology in this age and day.

Which from a systems perspective, is elegant but from a human one, it’s exhausting.

The issue isn’t that screens exist. It’s that they are engineered to behave like environments rather than tools, spaces you inhabit rather than things you use.

And unlike enterprise systems, there is no maintenance window.

Which leads to further the need of fighting for the limited resource us human beings have: attention.

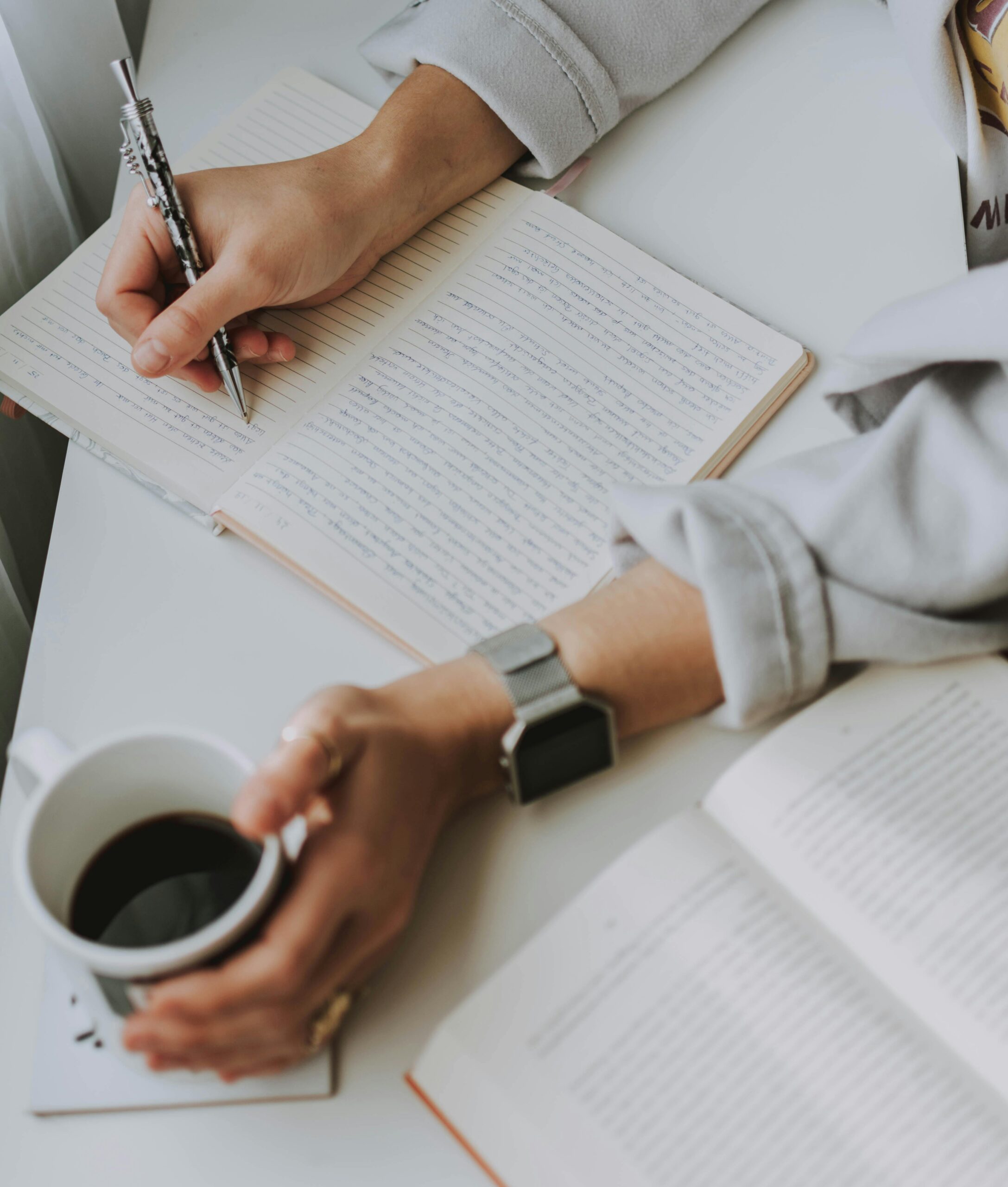

The Cognitive Load We Don’t Log

A few weeks later, I noticed it in myself. I’d reach for my phone between meetings, not to check anything specific, but to fill the gap. Five minutes became twenty. I’d return to work foggier than before.

In industry, we track latency religiously. Milliseconds matter. But we don’t have dashboards for mental residue or the cognitive drag that lingers after fragmented attention.

Research is beginning to quantify what many people feel intuitively. Studies link excessive screen switching to reduced working memory, impaired focus, and increased anxiety. Even short interruptions can leave “attention residue,” making it harder to fully re-engage with complex tasks.

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable. Their brains are still developing executive functions affecting the ability to plan, pause, and self-regulate. When systems externalize those decisions, the muscle doesn’t fully form.

We would never deploy production software that constantly interrupts its own processes. Yet we accept this behavior from the tools our kids use every day.

The False Comfort of Control

My instinct was to reach for controls. Screen-time limits. Filters. Monitoring software. Dashboards that promised visibility and command.

They helped but only superficially.

What they couldn’t address was the deeper issue: these systems are not neutral. They are designed with objectives that do not align with human wellbeing.

Rules can restrict usage. They cannot teach discernment.

Just as in cybersecurity, where the strongest defense includes user awareness, the real risk isn’t access. It’s unexamined interaction.

Teaching the Pause

The breakthrough came not from technology, but from conversation.

Instead of asking my nephew to “get off his phone,” I asked what made a video worth watching. Why some clips felt compelling and others forgettable. What it felt like when the feed ended versus when it didn’t.

At first, he shrugged. Then he started noticing patterns. Certain sounds. Certain pacing. Certain emotional hooks.

He didn’t stop using his phone. But he started pausing.

That pause is everything.

In systems design, we call it backpressure, a mechanism that prevents overload by forcing the system to slow down. Humans need the same thing, but internally.

We can’t rely on platforms to provide it. Their incentives are clear.

So we have to teach it.

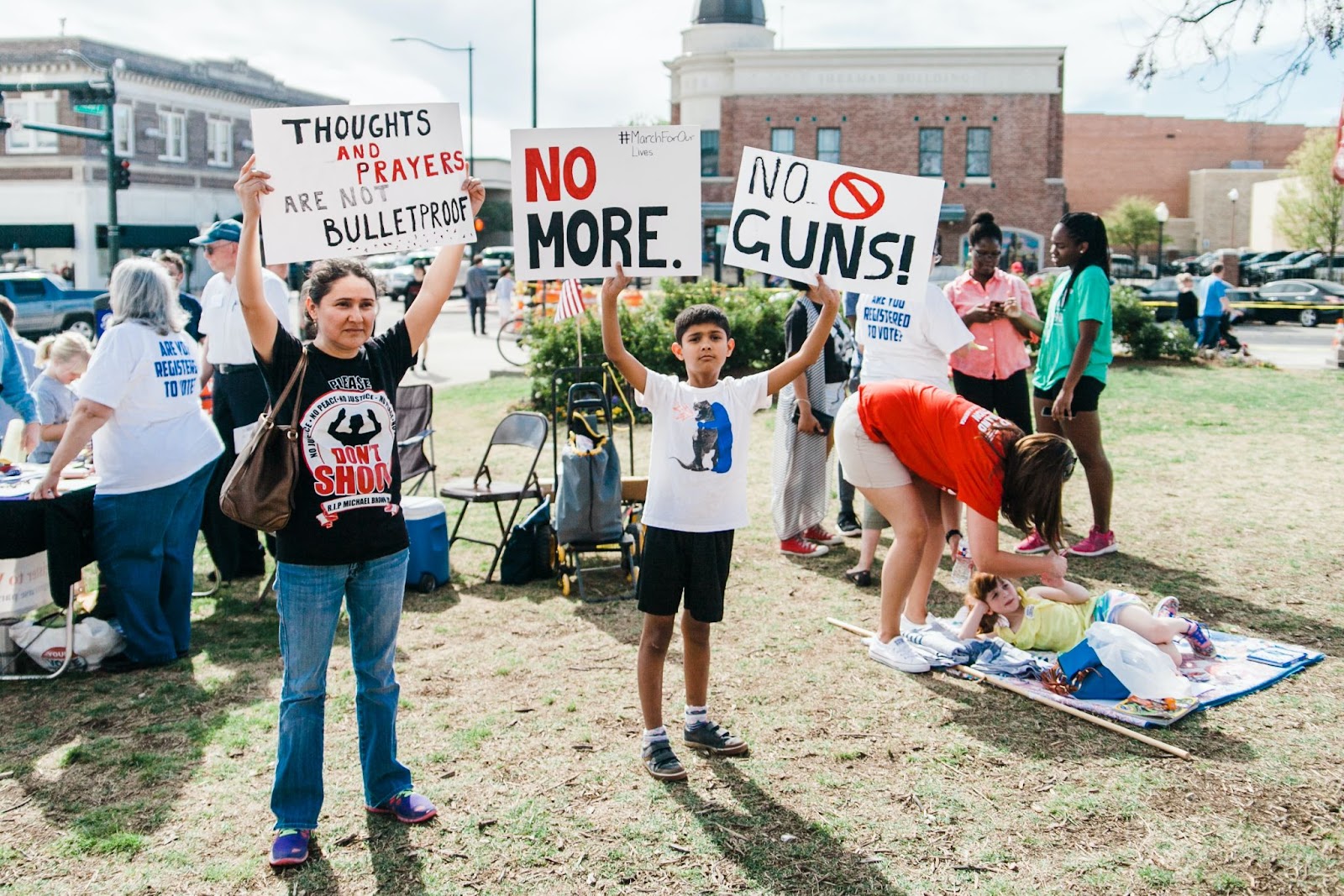

Rethinking What “Healthy Tech Use” Means

Healthy screen time isn’t about hours alone. It’s about agency.

Is the user choosing, or being carried? Is there awareness, or just momentum? Does the system serve a purpose, or has it become the default state?

These are not questions children or adults are taught to ask. Yet they are foundational to digital literacy in a world where attention is the most contested resource.

As professionals, we understand systems deeply and it is exactly this understanding that follows the philosophy that knowledge comes with responsibility especially when the users are developing minds.

Designing Humans, Not Just Systems

I still believe in technology. I build it every day. But I no longer believe that more engagement is inherently better, or that friction is always a flaw.

Some friction is protective. Some pauses are necessary. Some limits are not bugs, but features because our minds are evolved to disconnect and breath.

Watching my nephew now, I see moments when he puts the phone down on his own. Not because he was told to but because something clicked.

That click is the beginning of digital resilience.

We can’t roll back modern technology. But we can give the next generation what systems alone never will: the ability to notice when a tool stops serving them and the confidence to step away.

That is the best architecture we can build in this age of constant tiktoks and reels.

References[1] Muppalla SK, Vuppalapati S, Reddy Pulliahgaru A, Sreenivasulu H. Effects of Excessive Screen Time on Child Development: An Updated Review and Strategies for Management. Cureus. 2023 Jun 18;15(6):e40608. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40608. PMID: 37476119; PMCID: PMC10353947.

Written in partnership with Tom White