Image credit: Unsplash

Beyond merely planting food for consumption, Ron Finley is interested in planting food for thought. The self-described ‘gangsta gardener’ is no stranger to juxtaposing viewpoints or articulate conversations, which is the impetus behind his latest venture.

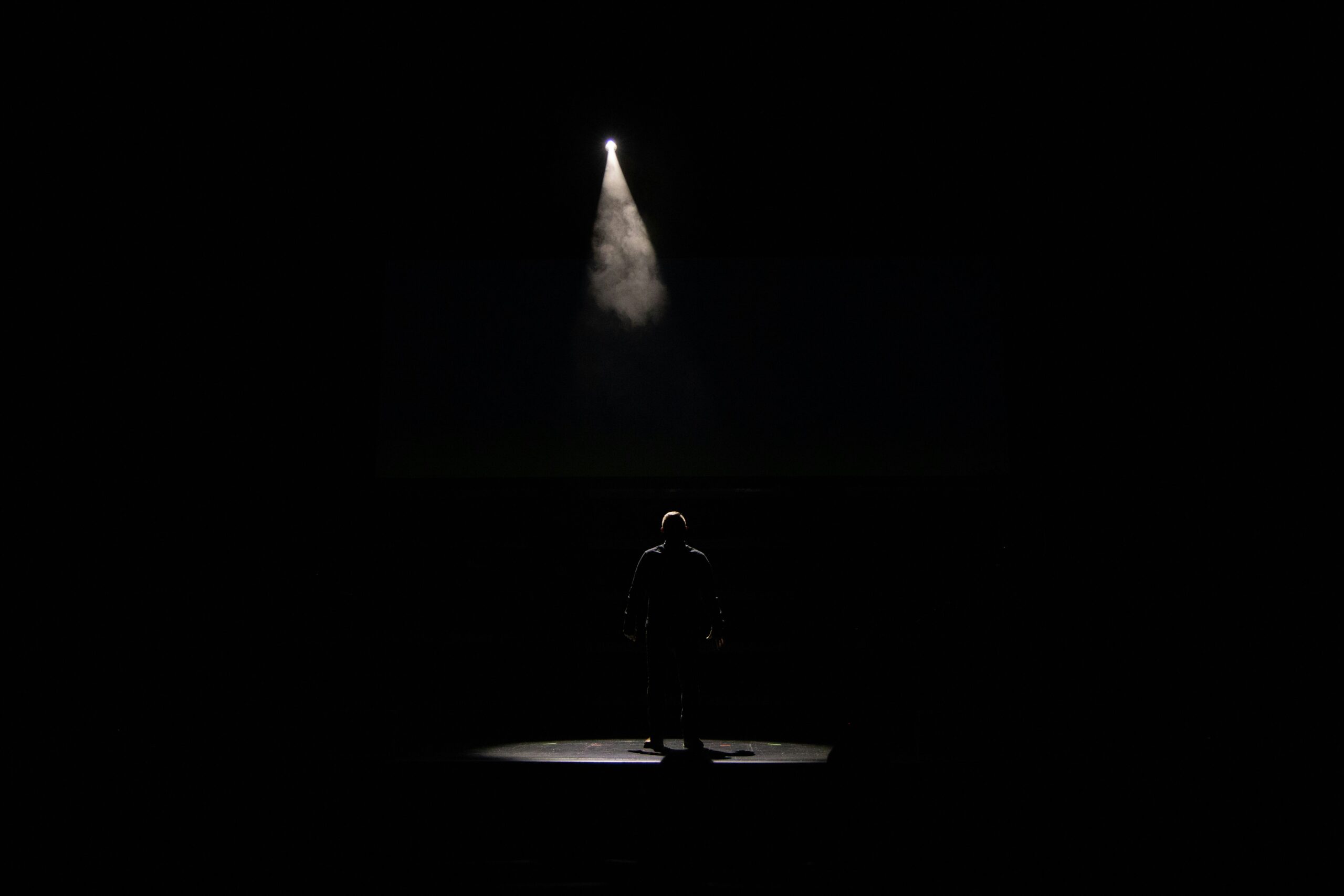

“This is what growing means to me,” he said, standing in front of a display he’s created on a terrace at the Hammer Museum. It includes a bathtub full of foliage, with the words “plant freedom” painted on the side. “That’s what I’m growing. I’m growing freedom.”

With his garden in South LA, Finley has tapped into urban farming as fertile ground for change that is perhaps most evident in one room at the Hammer, where art is planted like crops in neat rows. It’s a collection Finley calls Urban Weaponry, where he invited artists to transform shovels into statements.

“Weapons of mass creation instead of weapons of mass destruction,” Finley explained. “You want to change the world? Break the ground and plant something.”

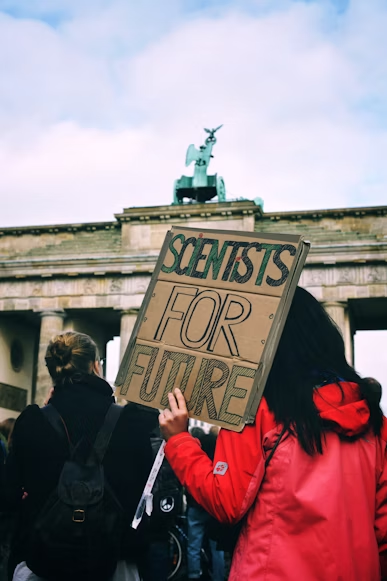

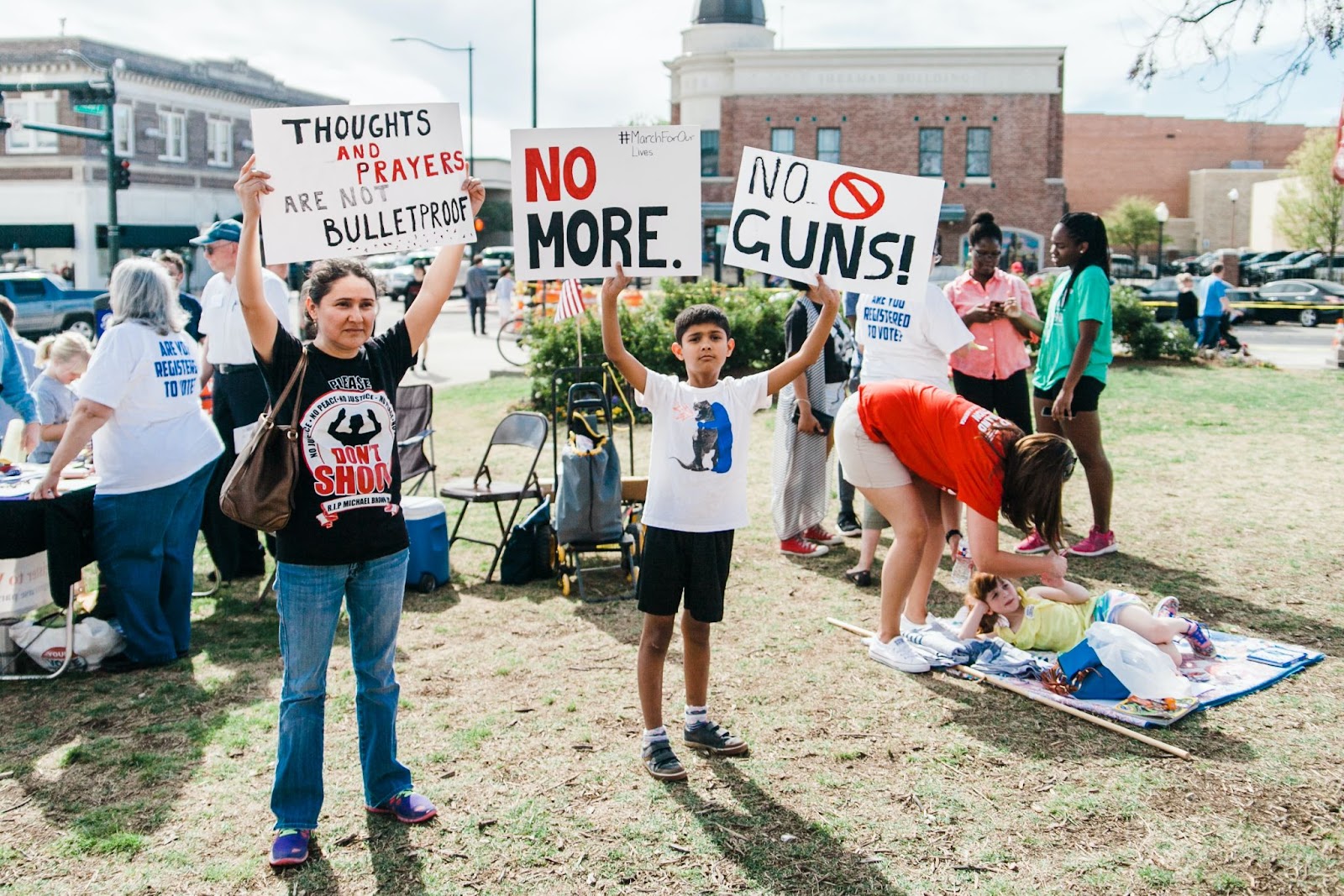

A major exhibition at the Hammer called Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice features roughly 100 works of art. When the curators began planning this exhibit for PST ART a few years ago, Glenn Kaino said they knew they wanted to focus on climate. But then, in 2020, the pandemic began attacking our respiratory systems, and George Floyd’s last words became a rallying cry.

“We realized that we couldn’t do a show about either without each other,” Kaino said. “There was an inextricable link between climate and social justice. And that’s how the concept of ‘Breath(e)’ was born.”

2020 Catlayzed into Art

In many ways, the year 2020 was something of a penultimate crossroads, which made the team realize that all of their passions and interests intersected in meaningful ways. In the same year that the George Floyd-fueled rallies took the world by storm, a pandemic spread around the world like wildfire, stealing people’s literal ability to breathe. In this way, Breath(e) became an art installation about finding meaningful beauty in the chaos of that period.

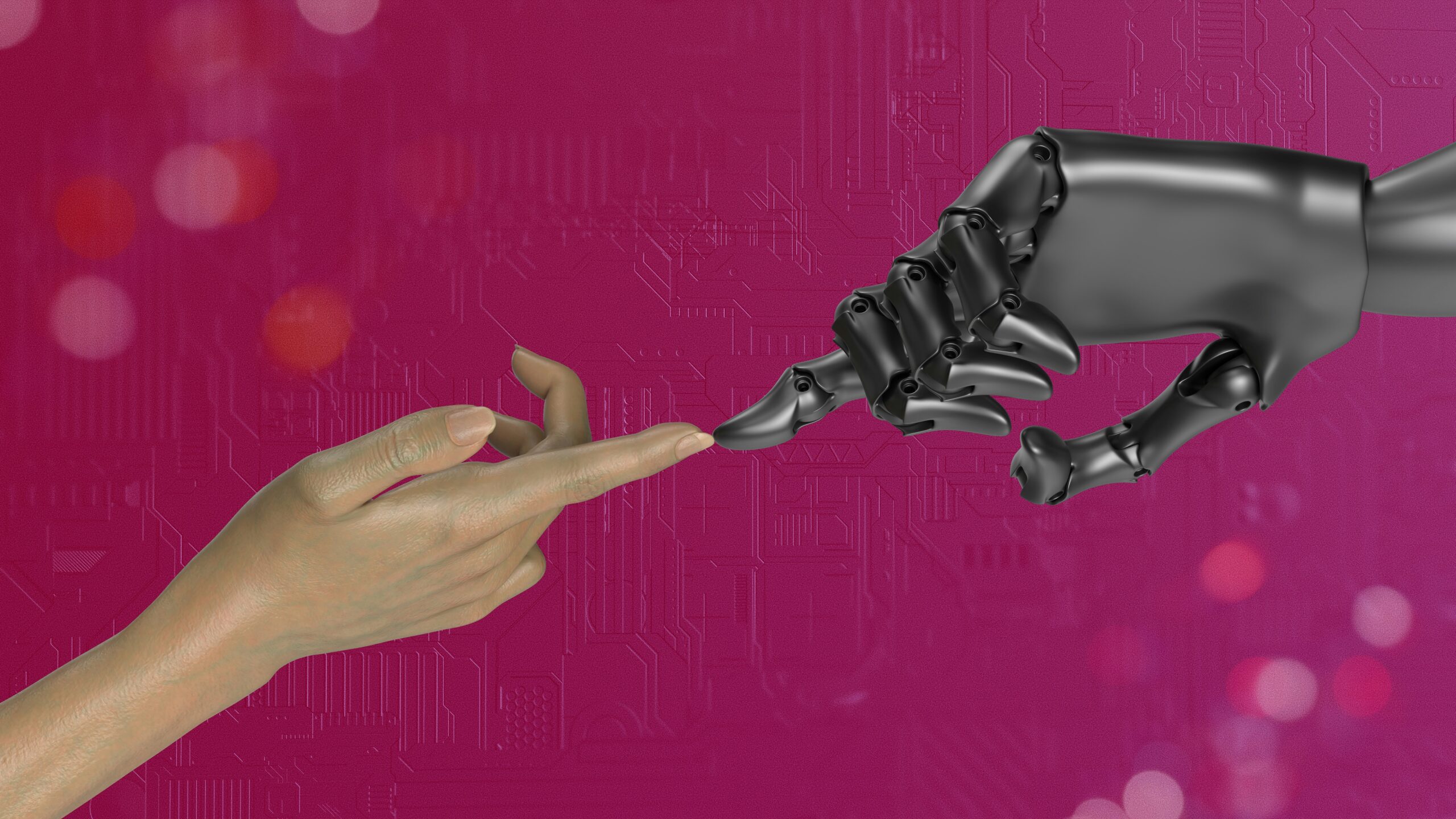

“The history of art and the history of science are really about humans understanding our world and each other better,” Kaino said. “What the Getty has done by providing resources to attack experimental problems is…What I believe art can do is to create a space of abstraction where very difficult problems can be attacked, and sometimes impossible solutions can be suggested.”

Although this incarnation of PST ART looks at what happens when art and science collide, Finley questions the kernel of that theme.

“I think art is science and art,” he said. “I think just because… we’re taught to think outside the box…why do you put us in a box in the first place? Try this. Ain’t no damn box. Why don’t we just think?”

Food for Thought

And that’s what he wants people to do in his garden. Think about climate and finding new uses for old items. Think about food deserts and social injustice. Think about the victims of police violence whose names are also planted among the greenery. And not just think. He included a table and chairs in his garden, inviting visitors to stay awhile.

“I want them to sit down and have a conversation with each other,” he explained. “It’s communal. I want people to engage.”

In a world routinely and monotonously overrun with rampant content creation and consumption, Ron Finley’s entire installation is engineered to allow guests to slow down and truly marinate in the ramifications and meaning of the art they are seeing. Finley hopes his work incites conversations and, by doing so, becomes a lasting part of those who have seen and experienced it.