Image credit: Unsplash

Over a span of 87 years, California’s wild wolf population stood at zero. In 1924, the last wild wolf was killed. It took until 2011 before another one of these creatures made its way across the Oregon border into the Golden State.

These days, gray wolves are reestablishing their presence in California. In 2024, the state’s population includes nine packs of up to 70 members, which is an increase from last year’s 44. Though most call California’s northeastern region home, one pack resides about 200 miles north of Los Angeles. Moreover, state wildlife officials estimate that as many as 30 pups were born this year, almost guaranteeing additional packs will form in the future.

Credit the Endangered Species Act

At one time, wolves held great prominence in North America. Before Western colonization, between 250,000 and 2 million of the revered canines roamed the continent. However, as settlers took hold, populations decreased as many states placed bounties on wolves. By 1915, Congress enacted legislation mandating that the animals be eradicated from federal lands.

In 1974, wolves were protected under the Endangered Species Act. From then on, the creatures began recapturing their hunting grounds and migrating from more northern locations.

“We didn’t reintroduce wolves into California,” said Axel Hunnicut, gray wolf coordinator for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “They came on their own.”

OR7

Hunnicut said that the first wolf to repatriate itself in California migrated from Oregon in December of 2011. The male animal was named OR7 because he was the seventh wolf radio-collared by authorities in Oregon. Over the next 13 years, the mammal’s population took off. Now, wolves appear in a greater number of places, even relatively close to large cities.

Controversy Reigns

This resurgence has precipitated much debate. While wildlife enthusiasts and conservationists view the growing population as a positive development, ranchers and farmers sing a far different tune. Members of these professions complain that wolves take out significant percentages of livestock and farm animals.

Research conducted in 2022 by educators at the University of California at Davis discovered that 86 percent of wolf scat contained cow fragments. In 2023, similar studies showed that 57 percent of these waste products contained pieces of cow.

Hunnicut said that these findings should not surprise anyone. Wolves are intelligent predators that will not waste their time going after larger, stronger animals. The UC Davis researchers also suggest that, believe it or not, wolf behavior has a psychological impact on cows that are not killed. Educators concluded that a wolf’s presence causes calves to gain less weight and cows to give birth less often. These events have serious financial consequences for affected regions.

In response, impacted parties have made numerous attempts to take wolves off the endangered list. Currently, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana permit a certain degree of wolf hunting. However, in California, the creatures remain protected and only continue to expand their influence.

“The majority of Californians will never see or hear a wolf,” said Hunnicut. “By and large, it’s the cattle ranchers in northeastern California who do. They wake up to wolves, they see wolves, they hear wolves, they have to live with the consequences of wolves eating their livestock.”

Opposition Support Keeps Dwindling

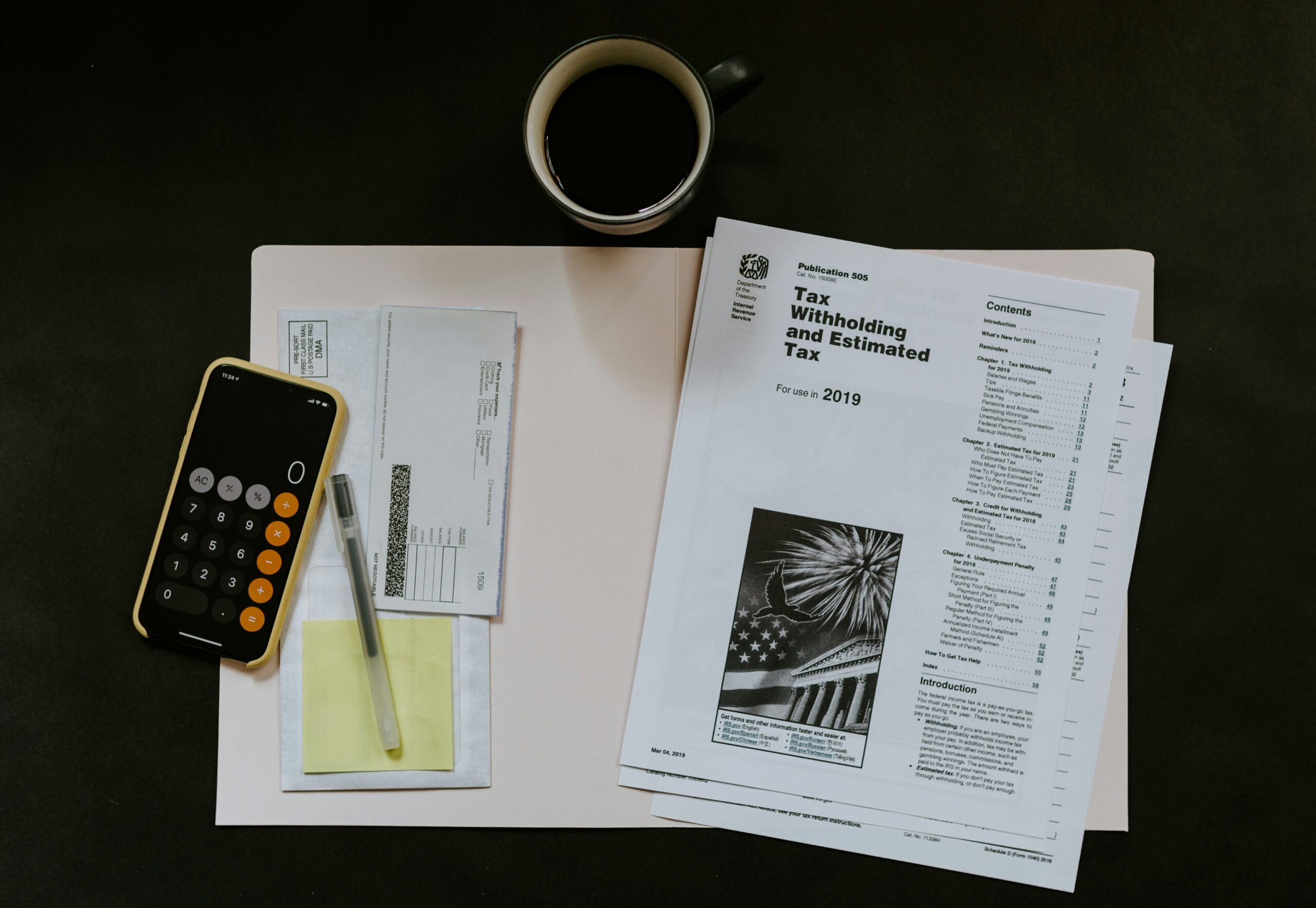

California created a compensation initiative to placate impacted ranchers and farmers, as well as enacted strategies designed to deter wolves from attacking animals like cows and calves. This program, called the Wolf-Livestock Compensation Program, provided landowners support for installing barriers such as flags and fences.

In 2021, state legislators approved $3 million for this purpose. However, this past May, those funds dried up. The state recently countered the funding shortfall by approving another $600,000 for wolf abatement efforts. Still, those in the farming and ranching fields argue that this amount is far too little to adequately address the problem.

Not an Easy Problem to Untangle

The wolves have not only had adverse social and economic impacts on California’s human population. The predators have disrupted the environments of other animals such as coyotes, bears, elk, deer, and mountain lions. Tina Saitone, professor of cooperative extension at UC-Davis, argues that when wolves reigned supreme in past times, human and animal populations were not as large, and therefore their actions did not have the same impacts as they do now.

“Nothing’s the same,” Saitone said. “We as a population have manipulated so many things, prey, predator, population. There are so many things that we can’t unravel.”