Image credit: Unsplash

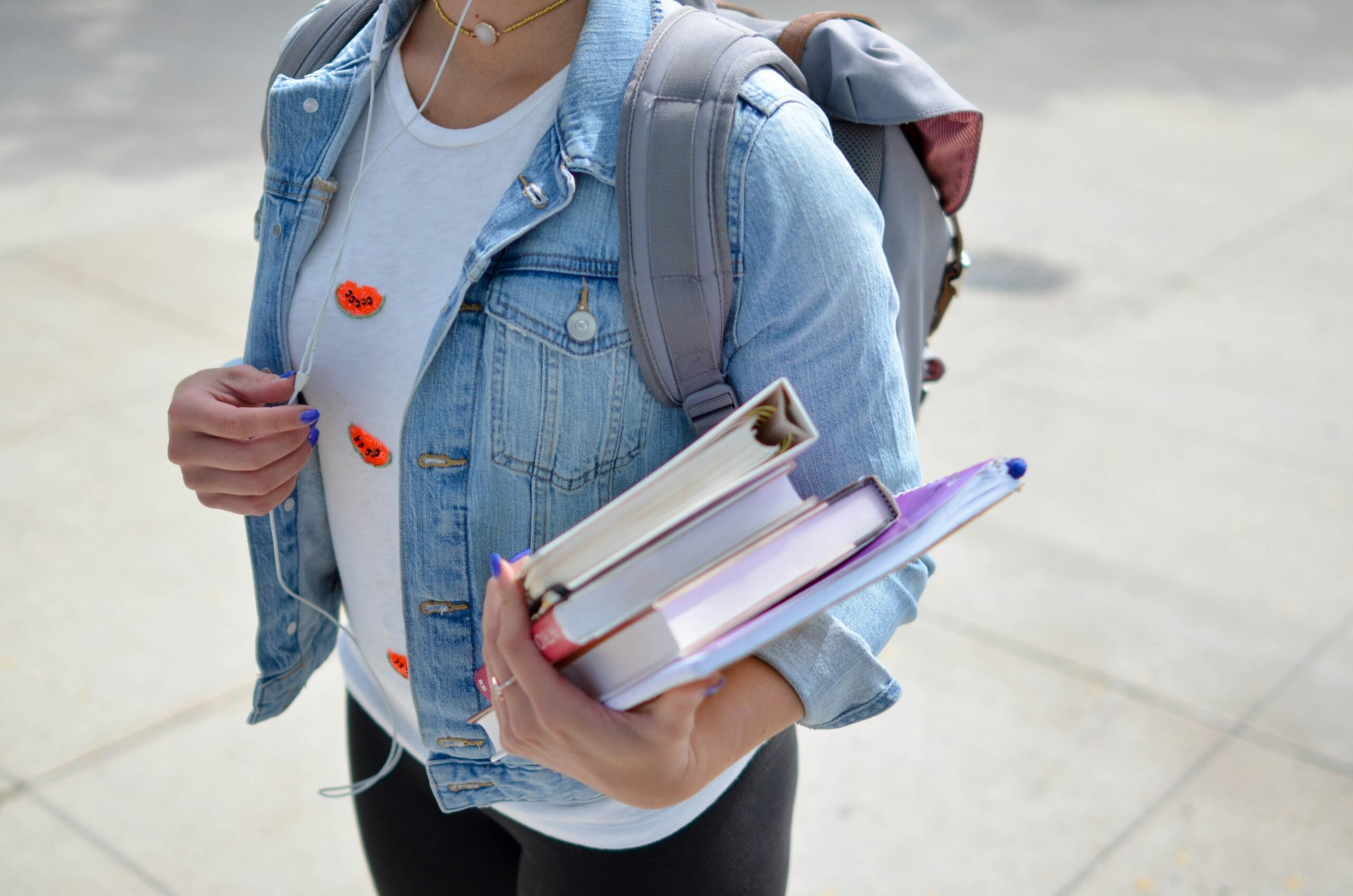

Studies of birth centers and at-home birth outcomes show that cesarean section and preterm birth rates decrease when trained midwives care for low-risk patients. So why are midwives being driven out of the state to stay in business? The answer lies in the way insurance companies pay them for their services.

Madeleine Wisner, a midwife who once offered services to patients at her Welcome Home Community Birth Center in south Sacramento, is one of the practitioners who is leaving the state of California after five years and over 450 births. This is in part due to the way that insurance providers reimburse women like her for their services.

“We’ve had people have two of three babies with us before we get paid for the first one,” Wisner said, after reporting that, on average, insurance reimbursed just 17% of the $8,500 cost for a full course of prenatal, birth, and postpartum care.

Though the Department of Health Care Services said in an emailed statement that it is working closely with the midwifery learning collaborative to help midwives provide services that will help them “successfully navigate and work” within Medi-Cal, the state’s low-income health program, service providers are still not getting paid promptly, leading to more and more midwives becoming frustrated with the system, and some leaving entirely. An effort to chip away at inequities, which was called the “California Momnibus Act,” requires Medi-Cal to cover postpartum care for a full year after birth, and even added doula benefits. The rate increases made these providers the highest paid in the nation. However, state regulations aren’t designed to accommodate the services that midwives in their communities provide.

“The overarching policy issue for licensed midwives in California is that we continue to be regulated under a very dysfunctional arrangement,” claimed Rosanna Davis, the president of the California Association of Licensed Midwives.

While the state is trying to make improvements, according to Holly Smith, the co-lead of the California Midwifery Learning Collaborative, the system is still “failing a lot of people.” The majority of patients born under Medi-Cal are babies of color. Both they and their mothers continue to suffer some of the worst infant and maternal health outcomes. State data shows that black women of all income levels are more than four times as likely to die from complications related to their pregnancies, and their babies are nearly three times as likely to die within a year.

46 hospitals have closed maternity wards since 2012. Holy Smith claims that, historically, state laws and policies have supported physician-only maternity care.

“It’s not safe anymore to do that,” she claimed. “We have a maternity desert situation. Literally hospitals are closing, and birth centers will be a necessary strategy for that.”

Midwives like Madeleine Wisner, who are leaving the state due to the lack of progress within California’s Medi-Cal system, wish that her birth center’s story had ended with a more positive outcome. Though her practice could have potentially been sustainable, she claimed that she did not want to argue with Medi-Cal insurers day in and day out. Now bound for New Zealand, she says that she and a team of other midwives will make $60,000 a year working only four days a week. In the end, Medi-Cal’s patients will be the ones most affected by their lack of action.